Korach and John Lennon

The Father of Spiritual Anarchy

By Yosef Y. Jacobson

Wise or Boorish?

Every folly has its kernel of truth. Every idea has a spark, a “melody.” It is just that you may be singing the right song at the wrong time, or conversely, the right song at the wrong time.

This is true concerning the tragic mutiny of Korach, described in this week’s Torah portion (Korach, Numbers chapter 16), the man who staged a rebellion against Moses and Aron, chosen by the Almighty to serve respectfully as the Prophet and as the High Priest of Israel?

“Korah was clever,” the rabbis declare, “so why did he commit such a folly”? The Rabbis were wondering, what propelled the wise Korach to declare war against Moses and Aron.

Their question is intriguing. How did the rabbis know that Korach was clever? Never has this person or his wisdom been mentioned in the Torah before? Whence the certainty that Korach was a wise man?

The answer, of course, is that the rabbis discerned the wisdom of Korach from this very incident. The very mutiny of Korach against the authority of Moses and Aron, demonstrate profound perception.

But why? On the surface, the mutiny seems to be a symptom of good old jealousy, of an unbridled ego craving power and fame.

No Distinctions

Korach challenged the authority of Moses and Aron, and the very structure of the community of Israel as ordained by G-d. But the principle behind his arguments was profound, and on one level, the ambition that fired his deeds was laudable.

“The entire community is holy,” argued Korach to Moses and Aaron in this week’s portion, “and G-d is within them. Why do you exalt yourselves above the community of G-d?”

These are powerful words. They resonate to many a mind. G-d is within each and every person. Why does anybody consider themselves spiritually superior to anybody else? Holiness, truth, grace, depth, integrity and transcendence are imbedded in each and every heart; the light of G-d can be found within me and within you. Within every pulsating heart flows the spiritual light, so why is Moses telling people what G-d wants? Why is Aron serving as the exclusive High Priest of G-d?

Why does a Jew need Moses to teach him the word of G-d and Aaron to perform the service in the Holy Temple in his stead, when he himself possesses a soul that is a spark of the divine flame? Why can’t he realize his relationship with G-d on his own, without teachers, leaders and priests in his spiritual life?

Korach is the father of spiritual anarchy. Korach argues against all forms of spiritual authority and leadership, and against any proscribed role in the spiritual community. Korach aspires to create a society free from distinctions, borders and categories. We are all divine, and hence we are all one.

Imagine there was no Moses, no Aron, no Sanctuary, no Kohanites, Levites or Israelites, and no religious authorities too… And the Jews would live as one.

And then from the Jews, Korach believed, the holistic energy-flow would travel to all mankind. And the world would live as one.

Korach’s message – let us confess — touches a deep cord in us. There is something about his vision that resonated deeply in our hearts. This is because Korach was dead right (which is why the Torah wants us to know about his ideology.)

But he was also dead wrong.

From Unity to Multiplicity and Back

We all come from one source. All of us originate in the “womb” of G-d, so to speak, where we are indeed singular. Before creation, there was only undefined unity. There were no borders, definitions or distinctions. No heaven, no earth and no countries. No teachers and students. All of us were submerged in the singular unity of the Endless Light.

On our deepest level, we crave to recreate this wholesomeness in our lives. We yearn for our egos to melt away in the singularity of existence. Remember the sense of ecstasy you felt in the good old times sitting with your friends in middle of the night, playing the music. There was no you or I; only the music.

Each of us, in our own way, pines to go back to that pre-creation paradigm of unity. We want to imagine that were never created.

But created we were…

The idea that all souls are the same was Korach’s mistake, and it is one of the mistakes of modern new-age spirituality. We are so used to thinking that definitions create barriers, and barriers cause hatred. We are convinced that to be spiritual means to have no borders.

But creation was the act of making borders. From unity came multiplicity. From a single undefined G-d, came an infinitely complex and diverse universe. Diversity is sown into the very fabric of existence. No two flakes of snow are alike; no two people are alike. There are tens of millions of different species of plants and animals in our world. And there are the inherent divisions between people, such as male and female, body and soul, and the specific divisions into nations, cultures and individuals.

Why did G-d create multiplicity? Because the deepest unity is the unity found within diversity. If we are all the same, unity is no achievement. In origin and essence, all is one. But an even deeper unity is achieved when differentiations and demarcations are imposed upon the primordial oneness, and its component parts are each given a distinct role in creations symphonious expression of the singular essence of its Creator. Like notes in a ballad, each of us represents a unique and distinct note, and together we recreate the symphony, not by singing the same note, but by expressing our individual note as an indispensible part of the song.

For the unity of humankind we need one G-d; but for G-d's unity to be complete we need human diversity, each individual fulfilling his or her role in existence, sharing with others their unique contribution, and learning from others the wisdom they lack on their own.

This is true on a political and sociological level as well. Many people believe that worldwide anarchy could lead to worldwide peace. Anarchy is certainly possible, but it is never peaceful, because conflict in the world is not the result of the division of our planet into countries and cultures. Conflict is the result of the truth that there exist inherent difference between peoples and then these difference compete, conflict is born. Therefore, our role as humans is not to deny that there are distinctions, but rather to create those types of borders and boundaries that will foster respect, unity and love within the inherent diversity of mankind.

Fusion

The Chabad school of Jewish spirituality takes it a step deeper.

G-d can’t be defined by unity or by multiplicity. Just as He transcends plurality, He also transcends unity. Therefore, it is only through the fusion of unity and multiplicity – through a place which transcends both of them — that we can connect to the true undefined essence of G-d.

If you choose unity and “worship” it, you are clinging to one aspect of G-. Conversely, if you embrace the ethos multiplicity, you are acknowledging another aspect of G-d. Only in the fusion of the two, only in discovering the unity within multiplicity, and the multiplicity within the unity, do you touch the undefined essence of G-d, which transcends and integrates all-ness and oneness, where nothingness and something-ness are one.

Swallowed and Consumed

Korach and his colleagues were swallowed by the earth. The 250 leaders of Israel that joined his mutiny were consumed by a flame. This is a psychological description of what happened to many an idealist who attempted to live by Lennon’s Imagine and imagination. It occurred to a whole generation of young passionate and beautiful Americans who worshipped and romanticized unity at the expense of all forms of authority, borders and distinctions.

The harsh, competitive reality of earth “swallowed” up much of their young idealism and selflessness. Their passion ascended in the flames of time, as they themselves were absorbed by the self-serving and egocentric demands of planet earth. From beneath the crust of the earth we can still recognize stretched out arms, silently asking the question, what happened to all of the love?

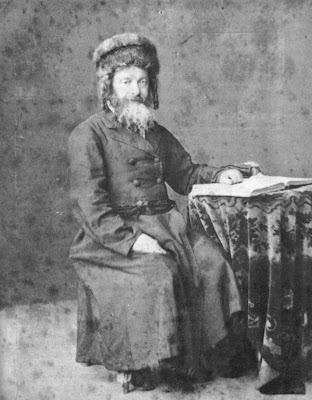

(This essay is based on an address by the Lubavitcher Rebbe in 1957 and 1971, published in Likkutei Sichot, vol. 18 pp. 202-211).